FAQs on the UN Tax Convention, international taxation and human rights

The United Nations Tax Convention (UNTC) process has ignited intense interest and raised numerous questions among organizations beyond traditional fiscal justice circles. As global discussions intensify around shaping fair and inclusive international tax policies, many are seeking answers and clarity on how this process impacts broader human rights and social and climate justice agendas. Here, we answer frequently asked questions about the UNTC, fiscal justice, and human rights.

Understanding international taxation

In today’s global economy, money and businesses move easily across borders. But tax authorities are still constrained by national boundaries. Each country has its own tax rules. When those rules are not well coordinated, it becomes easier for powerful actors to shift profits, hide wealth, and dodge taxes. Loopholes and lack of oversight create space for both illegal tax evasion and legal but harmful tax avoidance.

Originally, international tax rules focused on avoiding double taxation. Countries signed bilateral agreements to make sure the same income was not taxed twice. But over time, the focus has shifted. Now, multilateral efforts are trying to address the much bigger challenge: how to stop multinational corporations and ultra-wealthy individuals from abusing the system.

Today’s main challenges in international taxation stem from how multinationals and the digital economy are taxed, along with tax abuse by ultra-wealthy individuals. Multinationals exploit loopholes by shifting profits to jurisdictions with lower tax rates and strong financial secrecy, even when those profits are earned elsewhere. This is especially common among digital companies, which often have no physical presence in the countries where they operate. At the same time, rich individuals use offshore accounts, shell companies and trusts to hide wealth and lower their effective tax rates—often paying less than ordinary citizens.

This fuels a global “race to the bottom”. Countries are pressured to lower their corporate tax rates in order to attract foreign investment. That costs all governments revenue. But low- and middle-income countries are hit hardest. They lose funds that could otherwise support essential services. Local businesses face unfair competition. Public infrastructure suffers. Inequality deepens.

We use the term “tax abuse” to describe both evasion (which is illegal) and avoidance (which is legal but deeply unjust). This distinction is often blurry, but the impact is clear: nearly half a trillion dollars is lost each year—$311 billion by multinational corporations and $169 billion by wealthy individuals. Much of this loss is linked to illicit financial flows, which also involve corruption, bribery, and smuggling.

The impact goes far beyond balance sheets. Tax abuse undermines the very systems people rely on for healthcare, education, and clean water. It directly weakens states’ ability to meet their human rights obligations.

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) are movements of money across borders that are illegal in their origin, transfer, or use, or deliberately hidden to escape accountability. They include tax evasion, trade misinvoicing, profit shifting, money laundering, and corrupt practices such as bribery and smuggling. Each year, IFFs drain hundreds of billions of dollars from public coffers, with the greatest impact on low- and middle-income countries.

The damage goes far beyond lost tax revenue. IFFs erode transparency and accountability in fiscal systems, fuel corruption, and entrench inequality by allowing powerful corporations and wealthy individuals to avoid contributing what they owe. This weakens public trust and undermines governments’ ability to fund essential services such as health, education, and social protection. These are core pillars of human rights and development.

Confronting IFFs is therefore not just a technical challenge but a moral and political imperative. Tackling them is essential to mobilize public resources, curb corruption, and build fairer and more accountable tax systems that put people’s rights at the center.

Taxes and human rights: obligations and impacts

The full realization of human rights for all faces significant financing shortfalls, exacerbated by crises like climate change, unsustainable debt, and poverty, all of which require urgent collective action. Global tax abuse depletes government coffers, resulting in the underfunding of essential public services and under-resourcing of rights. Integrating human rights standards into taxation is vital because they are a fundamental part of the international legal framework and impose obligations on states, including to mobilize maximum available resources for human rights.

The Terms of Reference of the UN Tax Convention (UNTC) explicitly recognize alignment with States’ obligations under international human rights law as one of the guiding principles of the UNTC. This makes human rights standards a critical benchmark for evaluating tax systems and international tax cooperation, emphasizing the need for it to close inequalities and ensure governments can fulfill their human rights obligations.

Framing international tax cooperation through a human rights lens is key for adopting a holistic, sustainable development approach that addresses inequality, environmental issues, healthcare, gender equality, and intergenerational aspects. Human rights mechanisms provide crucial guidance for dismantling past injustices and building transparent, inclusive mechanisms for the future.

The commitments that States undertake upon ratifying human rights treaties, which are key for international taxation and tax cooperation, include:

-

Mobilizing maximum available resources for economic and social rights: Human rights norms require that every State mobilizes its “maximum available resources” towards progressively realizing economic, social, and cultural rights, including through international cooperation. To increase domestic resources, a progressive and equitable tax system is essential.

-

Extraterritorial obligations: States must not only realize rights within their borders, but also have duties prohibiting them from engaging in behavior that violates rights beyond their borders. Recognizing states' extraterritorial obligations is crucial because the international tax regime has far-reaching effects beyond national borders. Failure to acknowledge these obligations may allow states to evade accountability for actions that violate human rights elsewhere, thereby reinforcing the need for assessments of extraterritorial impacts.

-

Cooperation: The United Nations Charter recognizes the obligation of States to proactively cooperate globally towards collectively realizing rights-based development priorities. Cooperation among states is essential in international taxation as it promotes equitable, rights-based development globally. This cooperation is critical for realizing human rights and preventing actions that undermine states' capacities, particularly in developing countries, to fulfill their human rights obligations due to issues like tax evasion and avoidance.

-

Equality and non-discrimination: Principles of equality and non-discrimination widely recognized in international human rights’ law are crucial as they guide progressive tax reforms, wealth redistribution, and the promotion of gender equality with an intersectional approach. These principles ensure that tax policies are fair and contribute to financing public services without discrimination.

-

Transparency: Transparency is a fundamental human rights principle and is crucial in international taxation to prevent injustices such as tax evasion and avoidance. Lack of transparency enables practices that lead to significant revenue losses, particularly in developing countries. Upholding transparency principles ensures accountability and prevents unjust enrichment.

-

Inclusiveness and participation: Inclusiveness and participation ensure that all groups affected by fiscal decisions, especially historically disadvantaged groups, have a meaningful say in the tax process. Democratic tax-related procedures enable full, informed participation, ensuring that decisions are fair, equitable, and considerate of diverse stakeholder needs.

-

Progressive realization and non-retrogression: The obligation to ensure the progressive realization of economic and social rights by taking appropriate steps expeditiously and effectively, through ‘deliberate, concrete and targeted’ measures, ‘to the maximum extent’ requires not taking retrogressive measures leading to the deterioration of the enjoyment of rights. Retrogressive measures that would decrease the enjoyment of rights, such as reducing the budget allocated to public services, should be temporary, a last resort, and must give special consideration to impacts on the most vulnerable, according to the principle of ‘non-retrogression’.

Why global tax reform moved from the OECD to the UN

Originally, international tax cooperation was initiated under the League of Nations, the first global intergovernmental organization, founded in 1920 with the goal of maintaining world peace. The United Nations, established in 1945 in the aftermath of World War II, was the natural body to carry this work forward. But its role was sidelined by the rise of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1961. Often described as a “club of rich countries”, the OECD has since become the dominant actor in shaping global tax rules, particularly those affecting multinationals.

However, its legitimacy is increasingly questioned. The OECD’s limited membership (made up mostly of Global North countries) and its decision-making structure (which gives more influence to wealthier states) have raised concerns about fairness and inclusivity. The UN Secretary-General has echoed these concerns in his report on international tax cooperation, citing both the limited effectiveness of the OECD’s rules and their lack of legitimacy.

In the meantime, multinationals continue to exploit loopholes to avoid paying taxes in the countries where they do business. The consequences fall on ordinary people, who end up bearing the burden through higher taxes and weaker public services. The revenue lost to tax avoidance could have funded essential rights-based services such as healthcare, education and social protection.

The OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) is the main forum established by the OECD and G20 to respond to tax challenges arising from globalization and digitalization. It was also part of their broader reaction to the 2008 financial crisis and a series of scandals exposing widespread tax abuses by multinational corporations.

BEPS refers to the strategies used by multinationals to shift profits away from where real economic activity takes place, moving them instead to jurisdictions with little or no tax (so-called tax havens). The original BEPS package, launched between 2013 and 2015, set out 15 action points aimed at closing these loopholes. However, it was widely criticized for being overly complex, non-binding, and skewed in favor of OECD countries.

In 2016, the Inclusive Framework was introduced as a larger network (currently including around 140 jurisdictions) to oversee the implementation of BEPS measures and to develop new global standards. Its main initiative, often referred to as BEPS 2.0, consists of two parts or “pillars”:

-

Pillar One aimed to reallocate a portion of taxing rights over the largest and most profitable multinationals to the countries where their customers are located (known as “market” jurisdictions), even if the companies have no physical presence there. This applies only to companies with global turnover above €20 billion and profitability above 10 percent, and reallocates 25 percent of profits above that threshold.

-

Pillar Two introduced a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15 percent for companies with annual revenues above €750 million. This is intended to reduce harmful tax competition between countries. However, it allows for “substance-based carve-outs” (exemptions for profits linked to payroll and tangible assets) which further reduce the expected revenue gains—particularly for developing countries.

The implementation of BEPS 2.0 stalled. Pillar One has not been implemented at all. Negotiations broke down in 2024, largely due to U.S. objections that it disproportionately targeted U.S.-headquartered tech companies, and disagreements among other states on design and scope. Countries that had planned digital services taxes (DSTs) have delayed or suspended them, but no replacement mechanism is in force. In practice, Pillar One does not exist today.

Pillar Two has only been partially implemented. Around 40 jurisdictions have adopted laws, mainly in the EU and a few high-income economies, but enforcement remains patchy and loopholes abundant. Many developing countries have not implemented Pillar Two, and some have questioned whether the administrative complexity outweighs the small projected revenue gains. The U.S. has not enacted Pillar Two domestically and has instead pushed within the G7 for alternative arrangements. This stalled progress has reinforced arguments that tax reform cannot stay at the OECD and must shift to a universal forum like the UN.

These initiatives are deeply flawed. They fail to put people and the planet before corporate profits. UN experts have warned that the reforms risk undermining progress on economic and social rights and could violate states’ obligations to ensure equality and non-discrimination. For many governments and civil society organizations, including CESR and allies, these shortcomings confirm that global tax reform cannot remain under the OECD, which lacks both universality and accountability.

Pillar One was designed to address the long-standing challenge of taxing the digital economy. But the proposal has collapsed. Digital giants continue to operate across borders without being taxed fairly. Even if implemented, Pillar One would have applied only to the very largest corporations (those with more than €20 billion in global turnover). This means companies such as Amazon’s retail operations would have been excluded altogether.

Pillar Two introduced a minimum corporate tax rate, but the rate was reduced from early proposals of 20 to 25 percent to just 15 percent. Even this low threshold is proving difficult to enforce. Many countries have not signed on, creating gaps that multinationals can exploit. “Substance-based carve-outs” (exemptions for profits linked to payroll and tangible assets) have further weakened the policy and reduced its potential to raise revenue, particularly for low- and middle-income countries.

These reforms were negotiated mainly among OECD and G20 members, with limited input from developing countries. Although the United States was central to pushing the agenda, it has not implemented either Pillar, which further undermines their credibility. Despite broad participation, the system continues to reflect the interests of high-income countries, where most multinationals are based. According to the EU Tax Observatory, developing countries would gain only 0.17 percent of current tax revenues from Pillar Two. This is a negligible amount.

The United Nations Tax Convention (UNTC)

The United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation (UNTC) is the first global, treaty-making process on tax rules open to all countries. It marks a historic shift away from the OECD-led system, which has long excluded the Global South and helped entrench global inequalities. For decades, civil society and many governments have called for a fairer and more inclusive approach to global tax governance.

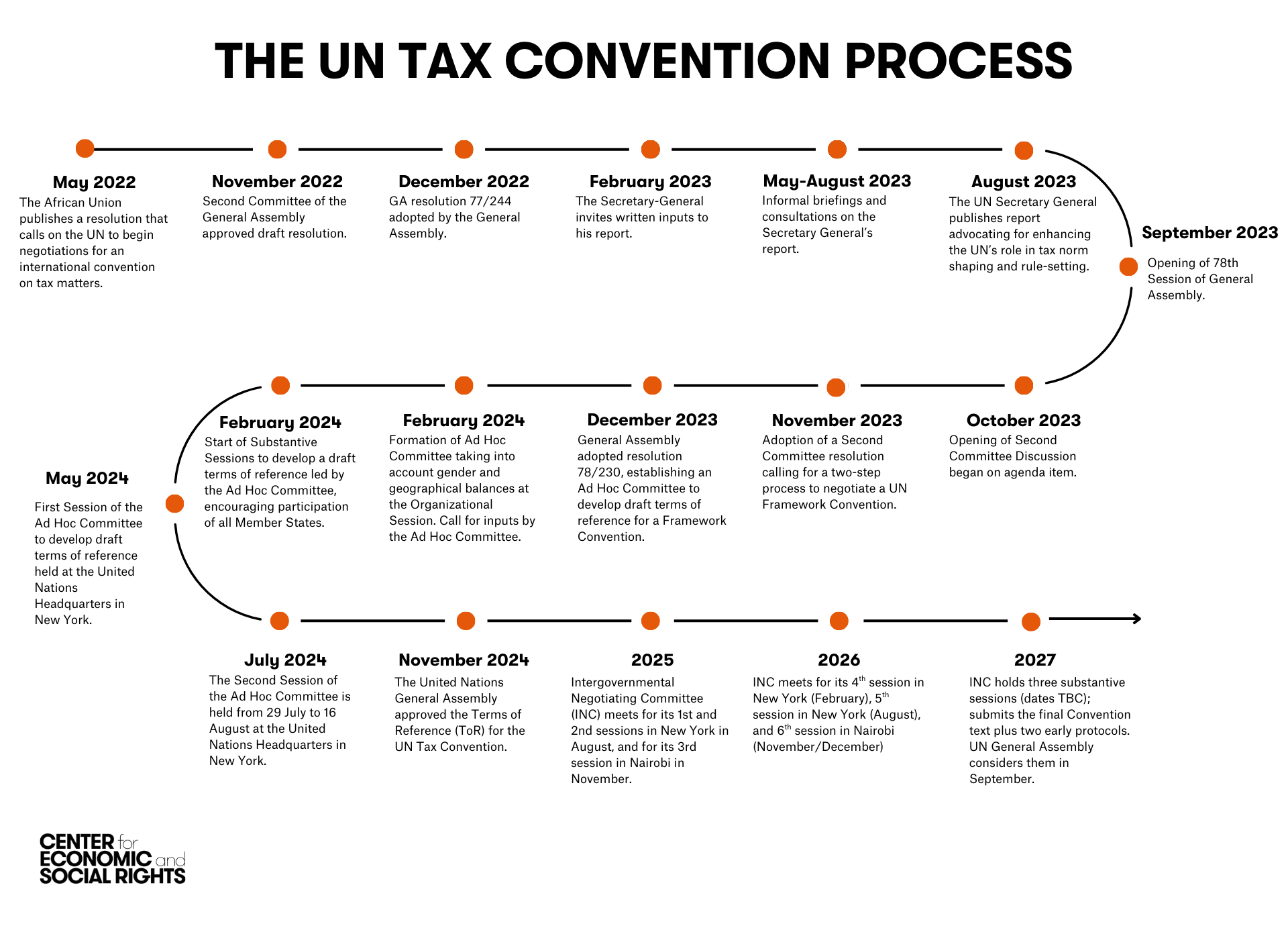

Momentum built in November 2022, when Nigeria, on behalf of the Africa Group, tabled a resolution at the UN calling for a UN-led tax process. Despite opposition from powerful OECD countries, the resolution passed with 125 votes in favor and 48 against, paving the way for negotiations in a universal forum.

In December 2023, the UN General Assembly created an Ad Hoc Committee to draft Terms of Reference (ToRs) for the new Convention. These were endorsed in November 2024, outlining goals such as fair allocation of taxing rights, tackling illicit financial flows, taxing the ultra-wealthy effectively, and aligning tax cooperation with human rights and sustainable development.

Negotiations formally began in August 2025 under the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee, which has since established a diverse bureau, rules for decision-making, and space for broad participation.

For countries in the Global South, the UNTC represents a long-overdue chance to rewrite global tax rules on equal footing, reclaim revenue lost to tax abuse, and advance economic justice through fairer international cooperation.

The International Negotiating Committee meets three times annually, focused on three parallel workstreams for the Framework Convention and its two early protocols (on protocols, see below):

-

Workstream I: The Framework Convention. This Workstream is focused on the core treaty text, building on the objectives, principles and commitments laid out in the Terms of Reference, as well as the institutional architecture of the UNTC, such as the Conference of the Parties (COP), Secretariat, subsidiary bodies, decision-making rules and review mechanisms. It is here that broader questions of fairness, transparency, capacity-building, and alignment with human rights and sustainable development commitments are being debated.

-

Workstream II: Protocol on the taxation of cross-border services in a globalized and digitalized economy. This Protocol will aim to set new rules for taxing income from services provided across borders. Current rules often require a physical presence before taxing rights apply, which is seen as outdated in today’s digital economy. This Protocol will therefore explore new nexus rules, source-based taxation, and whether revenues should be taxed on a gross or net basis.

-

Workstream III: Protocol on prevention and resolution of tax disputes. This Protocol seeks to establish mechanisms to prevent disputes before they arise (e.g. through stronger cooperation, transparency and information exchange) and to resolve them fairly when they do. It is where the controversy over arbitration versus state-to-state mechanisms is being discussed, alongside questions of accessibility, sovereignty and capacity constraints.

Together, these three workstreams form the backbone of the negotiation process: the Framework Convention provides the foundation, while the first two protocols test how detailed, operational rules can be agreed under the new system.

The negotiations are structured to last three years. According to the Terms of Reference, the Framework Convention and its two early protocols (on cross-border services and dispute prevention/resolution) should be finalized by September 2027, when they will be submitted to the UN General Assembly for adoption.

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee meets three times a year to develop the text. The first two substantive sessions took place in August 2025 and negotiators are working towards drafting a set of high-level commitments by the end of 2025. In between sessions, countries meet in virtual meetings of each workstream, roughly on a weekly basis.

The United Nations is the only global body with the legitimacy, universality, and mandate to ensure fair and inclusive international tax cooperation. It provides all governments with an equal seat at the table—a universal forum where states can work together to combat illicit financial flows, recover and return stolen assets, promote financial integrity, and mobilize resources for sustainable development.

Low- and middle-income countries have long been disproportionately harmed by tax abuse. These practices deprive governments of the resources needed to fund quality public services, fulfill their human rights obligations, and finance climate resilience and adaptation. Yet under current systems, their voices are often sidelined.

Moving tax rule-making to the UN opens the door to inclusive and participatory negotiations. Unlike the OECD, which reflects the interests of its 38 mostly high-income members, the UN can support rules that are based on where real economic activity takes place. This could lead to a fairer allocation of taxing rights, increased domestic revenues, and stronger public services in countries most in need.

The universality of the UN also makes it possible to align international tax norms with international human rights law. It offers a path toward substantive fairness—especially for low- and middle-income countries whose development is undermined by the current system.

This need for a UN-led process has been recognized explicitly in the Compromiso de Sevilla (the outcome of the 4th Financing for Development Conference in 2025), which called for continued constructive engagement in the UN Tax Convention process as a key step toward more inclusive and effective global tax cooperation.

Financing for Development (FfD) is the United Nations process for addressing the structural dimensions of the global financial system and mobilizing global resources to end poverty, reduce inequality, and achieve sustainable development. Since the first international conference in Monterrey in 2002, FfD has provided the main space for governments to agree on how to generate and use financial resources fairly and effectively (particularly for low- and middle-income countries).

Across its milestones (Monterrey 2002, Doha 2008, Addis Ababa 2015, and most recently Sevilla 2025), the FfD agenda has consistently called for more inclusive and effective international tax cooperation. The Compromiso de Sevilla reinforced this demand by recognizing that international tax rules are central to mobilizing resources for the Sustainable Development Goals and climate action. It emphasized the need to curb tax abuse, strengthen progressive taxation, and expand fiscal space for investment in human rights, health, education, gender equality, and climate resilience.

While many states are approaching the UN Tax Convention as a way to fix gaps in the existing system, others, particularly Global South countries and civil society groups, are pushing for more transformative reforms. These include:

-

Unitary taxation with formulary apportionment: Instead of relying on complex transfer pricing rules that allow multinational enterprises to shift profits into tax havens, this approach would treat multinational enterprises as single global firms. Their worldwide profits would be taxed as a whole and then apportioned across countries according to objective indicators of real economic activity (such as sales, employment, and assets). This would anchor taxing rights where profits are actually made, not just where companies are legally headquartered.

-

Taxing high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs): Proposals include coordinated rules to ensure the ultra-rich cannot escape taxation through offshore wealth, shell companies, or trusts. CESR and other civil society groups have stressed that HNWIs often pay lower effective tax rates than average workers, and that global cooperation is needed to address their delocalized wealth.

-

Progressive environmental taxation: Several states and civil society coalitions have argued for taxes that make polluters pay, including surcharges on fossil fuel profits or carbon-intensive industries. These are presented as tools both for climate finance and shifting incentives toward sustainable production.

-

Global transparency measures: Proposals such as a worldwide asset registry, public country-by-country reporting, and beneficial ownership registers are gaining traction as systemic reforms that would make both corporations and wealthy individuals more accountable.

These proposals remain politically contested, particularly by some OECD members and business groups, but they are becoming more visible in the negotiations. For civil society organizations and many Global South countries, they represent the only real path toward a fair, simple, and enforceable international tax system.

The UNTC Terms of Reference (ToRs) state that one of the objectives of the Convention is to “establish an inclusive, fair, transparent, efficient, equitable and effective international tax system for sustainable development.” Therefore, “fairness” in the UN Tax Convention is not only about the distribution of taxing rights between countries. It refers more broadly to whether international tax cooperation enables governments to raise and use revenues in ways that are consistent with human rights obligations and sustainable development goals.

The ToRs explicitly state that the Convention should be aligned with states’ obligations under international human rights law. Human rights bodies have already given guidance on what a “fair” tax system means in practice. They have found tax systems to be unfair when revenues are too low to fund rights and essential services, exemptions and loopholes undermine governments’ capacity to mobilize maximum available resources; over-reliance on indirect taxes worsens inequality, or tax policies fail to address growing economic and social disparities.

Seen this way, “fairness” means that international tax cooperation should expand fiscal space for rights and sustainable development, ensure equality and non-discrimination, strengthen transparency and participation, and prevent international rules from undermining states’ ability to fulfill human rights obligations. It is about building a tax system that serves peoples’ rights and collective development.

Structure and Governance of the UNTC

According to the Terms of Reference (ToRs) adopted in 2024, the Convention should establish both the commitments and the institutional framework needed for effective international tax cooperation. Substantively, it is expected to include commitments on the fair allocation of taxing rights, effective taxation of high-net-worth individuals, tackling tax-related illicit financial flows and harmful tax practices, and linking tax cooperation to sustainable development and human rights.

On the institutional side, the Convention will be supported by a Conference of the Parties (COP), a Secretariat, and subsidiary bodies. It should also include provisions on review, verification, dispute settlement, amendments, and the negotiation of protocols. Two early protocols — on cross-border services and dispute prevention/resolution — are being negotiated in parallel, with the possibility of more to follow.

The ToRs also emphasize capacity building and technical assistance, to ensure that developing countries can participate equally in negotiations and implementation.

In negotiations, governance has emerged as a critical area. Global South countries have stressed the importance of equal voting rights, clear procedures for decision-making, and institutional safeguards that prevent the dominance of wealthier states. They argue that the legitimacy of the UNTC depends on moving away from OECD-style arrangements where powerful countries effectively set the rules.

By contrast, some OECD members have pushed for consensus-based or hybrid models, warning that formal voting could generate divisions and reduce buy-in. Civil society groups, in their submissions, have countered that “consensus” often functions as a veto for powerful states and risks reproducing the exclusionary dynamics of the OECD. They have called instead for majoritarian fallback rules, transparent records of decision-making, and independent monitoring mechanisms.

There are also debates over the role of the COP. Many Global South states want it to be more than a procedural body, with authority to set agendas, adopt protocols, and oversee implementation, supported by a permanent Secretariat with adequate funding and capacity-building functions. Others prefer a leaner structure, focused narrowly on technical cooperation.

Across these debates, one point is widely agreed: the way governance is designed will determine the credibility of the Convention. Without inclusive, transparent, and balanced institutions, there is a risk that the UNTC could lose the trust of the very countries it was created to empower.

The Terms of Reference for the UN Tax Convention explicitly encourage the participation of international organizations, civil society, academia, and other stakeholders in the negotiations. They also stress the importance of drawing on the expertise and complementarities of existing institutions and forums.

In practice, however, participation has been uneven. While stakeholders have been able to submit written inputs and make statements in plenary, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) have been excluded from online sessions and “informal informals,” where much of the real negotiation takes place. This has led to concerns that critical decisions are being shaped in closed settings without transparency or accountability.

CSOs, many of whom were instrumental in building momentum for the Convention, argue that a truly democratic process requires full and effective participation of observers throughout the negotiations. Ensuring meaningful stakeholder engagement is not just a procedural issue but a matter of legitimacy. Civil society participation brings perspectives rooted in human rights, gender equality, climate justice, and development priorities that are often underrepresented in intergovernmental negotiations.

Protocols are legally binding instruments attached to a primary convention. In framework conventions, they allow countries to adopt more detailed and technical rules on specific issues over time, while the framework convention itself sets out the broad objectives, principles, and governance structures. States must first ratify the Framework Convention to join any of its protocols, though participation in each protocol is optional.

Under the Terms of Reference, the UN Tax Convention will include two “early protocols” negotiated in parallel with the Convention itself:

-

Protocol I – on the taxation of income from cross-border services in a digitalized and globalized economy. This Protocol aims to establish new rules for taxing services that are increasingly provided across borders, including digital services (provided by companies such as Uber, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, Youtube, Airbnb, etc.), where current standards based on physical presence no longer apply.

-

Protocol II – on the prevention and resolution of international tax disputes. This Protocol is intended both to strengthen cooperation between states to prevent disputes before they arise and to provide fair mechanisms for resolving them when they do occur. The goal is to reduce legal uncertainty and ensure consistency in the application of international tax rules. Globally, unresolved tax disputes are estimated to tie up over hundreds of billions in corporate profits, leaving governments unable to access revenue they are legally entitled to. For developing countries, which often lack the capacity to litigate against powerful multinationals, these disputes can mean critical losses for health, education, and infrastructure budgets.

These early protocols are expected to be completed by 2027. Beyond them, the ToRs envision that additional protocols could be developed on issues such as high-net-worth individual taxation, illicit financial flows, harmful tax practices, environmental taxation, or enhanced exchange of information.

The Framework Convention is the primary treaty: it sets the objectives, principles, governance arrangements, and high-level commitments for international tax cooperation. Protocols are separate but legally binding instruments under the Convention that provide more detailed, technical rules. According to the ToRs, a state must first become a party to the Framework Convention in order to become a party to any of its protocols, but it is not obliged to do the latter just because it is party to the Convention. In this sense, protocols are optional, but binding once a State becomes a party to them.

This framework convention and protocol approach is common in other areas of international law, such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (with the Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (with the Cartagena Protocol on biosafety). In these systems, the main treaty establishes a strong foundation, while protocols operationalize specific commitments over time.

In the UNTC, the level of detail in protocols will depend on how ambitious the Convention itself is. A strong framework with clear commitments on issues like fair allocation of taxing rights and taxation of high-net-worth individuals will allow protocols to build coherently on that base. A weak framework risks leaving protocols as fragmented side-deals with limited reach.

For a fuller discussion of how protocols work in framework conventions, see this explainer prepared by the Initiative for Human Rights in Fiscal Policy.